Cuba remains a small country with an out-sized influence on global affairs. It continues to face many of the challenges of developing states, with which it has been traditionally aligned since the revolution of 1959. It’s political-economic model retains much of the flavor of Soviet Marxist-Leninism lingering long after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Cuba has managed to retain a continued enmity of the United States, even if the intensity of that enmity–expressed in law, politics, and economic policy–which waxes and wanes with succeeding American Administrations. During the same period it has led various coalitions of developing states, as it has sought to assert a leadership role among developing states. At the same time it has been an influential voice in important public international organizations within the United Nations, while cultivating an enmity to others, particularly international financial institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, to an art form.

Cuban political theory has been despised by many and yet it has influenced others. Cuba has long sought to deepen its autonomy even as it has moved from an uncomfortable dependence first on the Soviet Union, and then on a variety of other states most of whom welcomed the opportunity to use Cuba for their own interests especially when those interests were opposed to those of the United States. Cuban has become increasingly food insecure over the last several decades, even as it has become an important participant in global pharmaceutical research and development. At the same time its critics believe that some of this development is more propaganda than substance. Its has become less dependent on cash crops even as it became more dependent on tourism. Global social media remains fascinated by the idea of Cuba. The glow of its history especially on the cusp of the 1959 Revolution has helped to preserve portions of Havana’s historic district even as large portions of Cuban housing deteriorates at alarming rates. Cuba’s revolutionary heroes are household names virtually everywhere on earth even as its human rights record has been the subject of criticism from those same actors. This has been acutely evident in Europe, though in other places there has been a divide between those who embrace Cuban political theory, and those who embrace the theory that Cuba is a global violator of human rights.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic at the start of 2020, Cuba and its friends and neighbors had been functioning within the framework of a broad equilibrium. American enmity was matched by the friendship of Venezuela, China, China, and Iran, while European provided a measure of protection to take the edge off of American efforts to destabilize the government. Internally, Cuba elite continued to refine its Caribbean variant of Marxist-Leninism, one substantially suspicious of markets. Yet the resulting formal structures of the economic system also provides a space for an informal economy tolerated because it is the price of stability, and useful because it provides a means of disciplining the population when it suits the state. Cuba’s search for hard currency and global influence produced programs of providing medical services to other states (Cuban medical internationalism), which competitor states (and some of its participants) criticized for potential violation of human rights. Even this description can be incendiary precisely because Cuba lends itself to polarization of opinion. For example, while some are convinced that Cuban medical internationalism is deeply embedded within the political premises of Cuban Marxist Leninism, others believe that it constitutes a form of modern slavery in breach of the ILO conventions. And economists deride analysis describing declining economic growth as a broad equilibrium.

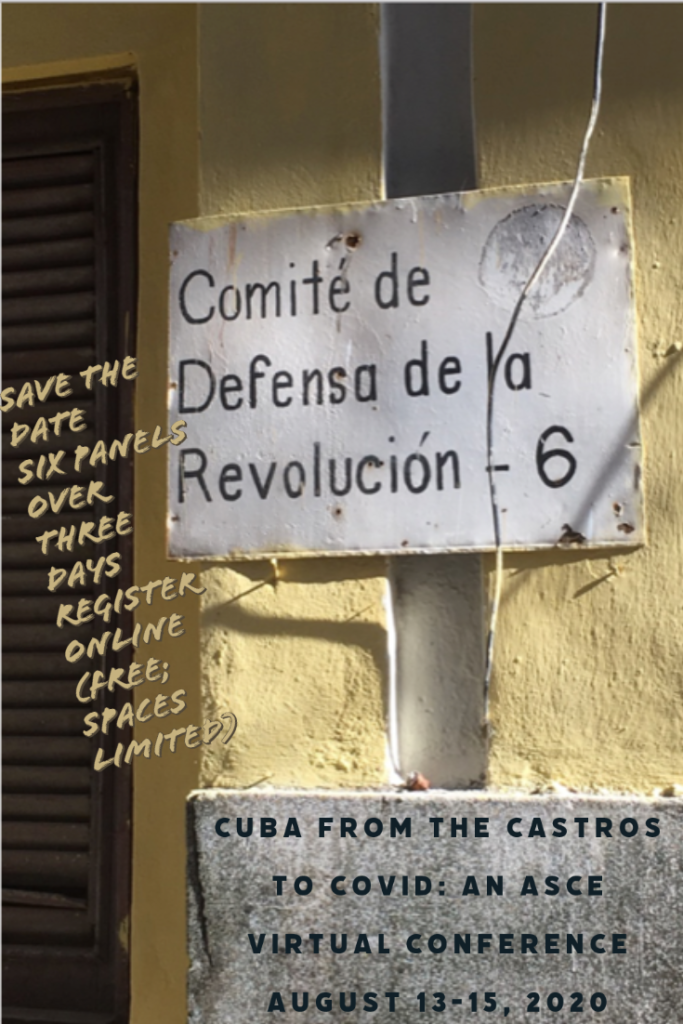

All of the delicate components of these external and internal balancing, the aggregation of which defined the state of the nation (its economics, politics, law and social ordering), have been substantially disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This conference has been organized to consider some of the more important aspects of that disruption and its potential consequences for the Cuban state, Cuban society, and its economics and international affairs. Participants will consider (1) The Cuban Economy and Prospects after COVID-19; (2) The Cuba Venezuela Relationship; (3) “Destrabando” the Cuban Economy: An Assessment of Reforms and the Road Ahead; and (4) a Roundtable on Developments in Moving Beyond Cuba’s Dual Currency System. The featured event, the Carlos Diaz Alejandro lecture will be given by the annual Carlos Diaz Alejandro Lecture. This year’s lecturer is Alejandro de la Fuente, Harvard University, who will speak to “Racism with Equality? Measuring Racial Inequality in Cuba, 1980-2010.” Lastly, ASCE will recognize a group of extraordinary students whose papers will be presented to end the conference.

Return to Conference Homepage